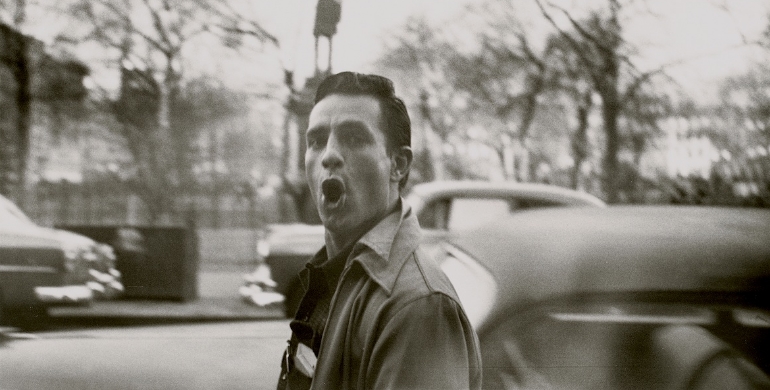

Aleister Crowley (via Mysteries of Paris)

English occultist Aleister Crowley led a raucous life as either a great charlatan or the “Great Beast 666.”

Besides the Devil, who famously convinced the world that he doesn’t exist, the greatest man of the left-hand path was Aleister Crowley. Born Edward Alexander Crowley in 1875, he would go on to become so infamous that he received the dubious honor of being the “Wickedest Man in the World.” While that would be quite enough for some people, it was actually a demotion for Crowley, who had given himself an even grander title years prior.

In the “Book of Revelation,” there are two beasts, one from the sea and one from the earth. The one from earth is given the number 666 and the power of a false prophet. This is the monstrosity that will challenge Christian faith before the Day of Judgement. This is the fiend that Crowley modeled his image after when sometime during the height of his fame he dubbed himself the “Great Beast 666.”

Many people at the time believed that Crowley was a committed Satanist and a prophet of devil-worship. In reality, he proselytized the worship of himself and of his own religion, which he called “Thelema” and which even had its own central tome, The Book of the Law. In an age when occult theologies and philosophies were being eagerly gobbled up by the intelligentsia and the general public alike, Thelema stood out because of its extreme libertinism and because of its very simple tenet: “Do what thou wilt.”

The sheer volume of newspaper and magazine features about Crowley (most of which can be found at The 100th Monkey Press) testifies that he was no recluse or wilting violet. Biographer Martin Booth has called Crowley “self-confident, brash, eccentric, egotistic, highly intelligent, arrogant, witty, wealthy, and, when it suited him, cruel.” But was he a liar?

There are so many stories about Crowley that it’s hard to distinguish history from fantasy. Let’s start, then, with what we know for sure:

Crowley during his Cambridge years (via Aleister Crowley 2012)

Just the Facts, Crowley

Crowley was born into a very strict Christian household that expressly forbid everything he would later champion. His family came from rural wealth, with his father owning part of a brewing business. Both of Crowley’s parents were strict disciplinarians who openly chastised their son as “the Beast of Revelation” because of his ill-temper and his unwillingness to conform to their strictures.

Crowley’s father died of cancer in 1887, leaving 11-year-old Aleister in control of a third of the family fortune. Young, wealthy and hedonistic is never a good combination, and following his father’s death, Aleister’s problems with discipline intensified. He wouldn’t stay in school past a few terms, and much to his mother’s shame, he began to openly revolt against Christianity. Like any petulant teenager today, Crowley started smoking, drinking and having more sex than a field rabbit. At some point, his dalliances with prostitutes won him gonorrhea, a fact he immortalized in an explicit 1920 poem entitled “Leah Sublime.”

Young Aleister was more than a simple ruffian, though. At about the same time as he was indulging in what were to become life-long vices, Crowley was also developing other interests, namely chess, poetry and mountain climbing.

While at Cambridge from 1895 to 1898, Crowley changed his name from Edward to Aleister and changed his scholastic focus from philosophy to English literature, which wasn’t even on the curriculum at the time. (In this sense, Crowley could be considered the first crazy English undergrad — and his lineage still thrives across the world today!) To the surprise of no one, Crowley proved to be an uninspired student. Like Max Fischer in Rushmore, Crowley’s college years were mostly consumed by extracurricular activities. From making a serious study of chess to beginning his career as a published poet, Crowley in Cambridgeshire was anything but lethargic. On top of this, he still kept up his vigorous sex life with prostitutes and the occasional male lover (he was later very candid about his bisexuality), and again, sometime between 1896 and 1897, Crowley contracted an STD, this time syphilis.

Crowley on his 1902 K2 expedition (via Wikimedia Commons)

After leaving Cambridge, Crowley traveled throughout Europe, even going so far as to visit the Russian city of Saint Petersburg. He continued mountain climbing as well, and in 1902, he and his frequent climbing partner Oscar Eckenstein attempted to climb K2, the second highest peak on Earth. Crowley, Eckenstein and their team made it to an approximate altitude of 20,000 feet before being forced to turn around.

As Crowley’s career in mountain climbing was reaching a plateau (he would later attempt to scale Kangchenjunga, the third highest mountain on Earth, but his partners mutinied and some porters died trying to climb back down in the dark), his interests in Western esotericism were just beginning. In 1898, he joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a British occult society dedicated to studying ceremonial magic, alchemy and metaphysics. Crowley proved to be a quick study in magic and ritual. Before long he was earning his way into the order’s inner circle, but his unpopularity kept him back. Even in an exclusive club dedicated to the occult, Victorian mores ruled. Members disliked Crowley’s sexual excesses and his recreational use of drugs. One member in particular despised Crowley: W. B. Yeats. (Rumor has it that the “rough beast” in Yeats’s “The Second Coming” is in fact Crowley himself.)

Beginning in 1900 and lasting several years, Crowley traveled the world studying various forms of mysticism. He learned Buddhism and yoga in India, and while in Egypt on his extended honeymoon he tried to invoke ancient Egyptian gods.

Stele of Ankh-ef-en-Khonsu (via Wikipedia)

In 1904, Crowley claimed that he did in fact make contact with one of these gods, the falcon-headed Horus. According to Crowley, his wife Rose, while under a trance, led him to a Cairo museum where the Stele of Ankh-ef-en-Khonsu, a painted wooden slab, sat as museum item number 666. The stele, which depicts the sun god Re seated on a throne before a Theban priest, supposedly allowed for the disembodied voice of Aiwass, a messenger of Horus who is exclusive to Thelema, to dictate to Crowley a new religious codex for a burgeoning eon. This ghostly communication produced The Book of the Law and designated Crowley as the chief prophet of a post-Christian world. His new purpose, then, was to communicate to humanity the power of their “True Will,” or their destined path in life in accordance with the secret workings of nature. As Thelema expanded, Crowley would add more volumes to his “Holy Books of Thelema,” but The Book of the Law remains the foundational text.

Crowley’s activities didn’t stop with the founding of Thelema. Besides continuing to write prolifically on the occult, Crowley also began publishing short horror stories and even wrote the novels Diary of a Drug Fiend and Moonchild. In 1912, Crowley became the head of the British branch of the Order Templi Orientis, a German occult society that practiced sex magic. Crowley incorporated Thelemic ideas into Order rituals and even composed a Gnostic Mass for combined ceremonies. The height of Crowley’s religious activities came after World War I, when he and others established the Abbey of Thelema at the Sicilian city of Cefalu.

By all accounts, the Abbey of Thelema was a constant Bacchanalia with heroin, prostitutes and sex magic rituals being freely available to the children of Crowley’s followers. Some male followers were forced into having anal sex with Crowley, while others, like the doomed Raoul Loveday, were forced to drink cat blood and even urine.

Loveday would eventually die of liver infection after drinking both Crowley’s devilish mixtures and the unsanitary local water. His wife returned to London and told the British press all about the Abbey of Thelema, and because Crowley, now destitute after a spendthrift life, could not afford the legal services necessary to prosecute for slander, the bad press against him continued without resistance. When the new government of Benito Mussolini learned of the accusations against Crowley, they served him deportation papers and forced the Abbey of Thelema to close its doors for good in April 1923.

For the remainder of his life, Crowley would be dogged by ill health and his many addictions. Still, he continued to travel throughout North Africa and Europe. During World War II, he composed patriotic verses in support of the British cause, all the while naming successors to the Order Templi Orientis, which had been dismantled by the Nazis. In 1947, at the age of 72, Crowley died after a protracted battle with lung infections and heart disease.

Crowley in Golden Dawn garb (via Wikipedia)

The Myth of the Great Beast 666

With a life as alternatively productive and sordid as Crowley’s, fantastic stories are inevitable. And since he was keen on cultivating a cult of personality, it only stands to reason that Crowley loved the myths that swirled around his name like so many phantoms. Detailing all the whispered rumors about him here would be too exhausting, but these tales are musts:

Raising Demons in Scotland

In November of 1899, Crowley purchased Boleskine House in Scotland. Located on the southern side of Loch Ness, the former hunting lodge served as his primary residence until he was forced to sell it in 1914. Boleskine has acquired a sinister reputation over the years because of the black magic ceremonies that Crowley supposedly conducted there. Specifically, many claim that he used it as a secluded spot for raising demons. According to Crowley himself, his activities at the lodge got out of hand and the spirits that he raised there were directly responsible for a series of tragedies, such as a local butcher who bled to death after accidentally severing an artery.

Long after Crowley left Boleskine, the property was purchased by Led Zeppelin guitarist and Crowley enthusiast Jimmy Page. Page conceived of a restored Boleskine as a perfect place to write songs, and many claim that the mystical elements and strange symbols presented on the cover of Led Zeppelin’s untitled fourth album were inspired by Page’s brief stay at the lodge.

Stranger still, in an article from Dangerous Minds, writer Paul Gallagher claims to have met a man in Los Angeles who believes that the demon Crowley raised at Boleskine became the Loch Ness monster.

Summoning Pan

Dennis Wheatley, the British thriller writer who used Crowley as the template for his devil-worshipper Mocata in his novel The Devil Rides Out, is the man mostly responsible for this myth. In The Devil and All His Works, Wheatley claims that Crowley and his followers rented the entire floor of a small Parisian hotel for a weekend-long ceremony to call forth the Greek god Pan. According Wheatley’s account, which he in turn claimed came from those who were there, Crowley successfully brought Pan back into the world, but could not control him. The other magician in the room with him was killed, while the whole ordeal left Crowley a “gibbering idiot.”

Wheatley’s account is more than likely sensational, and it more or less conforms to the earlier rumors about Crowley’s time at Boleskine. Still, this story does offer a window into how powerful some people believed Crowley to be.

Crowley (via Aroldo Paiva)

The Devil was a Spy

Of all the theories about Crowley, the idea that he was a lifelong member of British intelligence has the most legs. Entire books have been written about Crowley’s supposed work for the British government, and in a 1919 newspaper article he himself claimed that he was “in the confidential service of the British government” during the First World War.

This conspiracy theory goes a long way in debunking the idea that Crowley was a serious occultist. Some biographers, such as Richard Spence and Tobias Churton, believe that Crowley began working as spy while still at Cambridge and that all of his subsequent traveling was done partially under the commands of Downing Street. From claiming that Crowley’s relationship with the Golden Dawn was a mere ploy to get close to the Carlist-sympathizers to undermining the idea that his pro-Irish and pro-German sympathies during World War I were anything but field work done in order to weaken the credibility of those causes, the Crowley-as-spy concept is truly all-encompassing.

The most famous theory regarding Crowley’s government work is the notion that Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond and a real Naval intelligence officer during World War II, almost got permission to use Crowley as an interviewer during the interrogation of Deputy Fuhrer Rudolf Hess. In 1941, Hess, one of the most powerful men in the Nazi party, crash-landed in England in a failed attempt to get Great Britain to negotiate a peace with Germany. After being captured, Hess was removed to Scotland for interrogation. According to the rumor, Fleming and his boss decided that Crowley would be the perfect person to exploit Hess’s interests in the occult for Britain’s gain. Unfortunately, it’s more than likely that this plan was never conceived. Donald McCormick, a huckster journalist, is the likely culprit behind the story

But it still remains that Crowley did indeed know many members of both the British and American intelligence services. While one of his hand-chosen successors in the Order Templi Orientis was the American army officer Grady McMurtry, Crowley was also acquainted with Roald Dahl and Dennis Wheatley, both of whom spent World War II as intelligence officers attached to the Royal Air Force and the Royal Navy respectively.

Crowley (via Wikipedia)

Many of Crowley’s contacts in the British secret service also just so happened to be writers, and it’s well known that Crowley served as the model for many villains in the British potboilers of the 20th century. The first to use him was W. Somerset Maugham (who would later serve in military intelligence during World War I) in his 1908 novel The Magician. In it, Crowley appears as Oliver Haddo, a corpulent wizard whose home is scattered with tubes full of the homunculi that he himself created. In a 1911 tale by British ghost story writer M. R. James, the figure of Crowley is called Karswell, and in “Casting the Runes,” Karswell attempts to send a demon after his enemies.

While these characters, along with Wheatley’s Mocata, are obvious nods to Crowley, it’s not common knowledge that Crowley also inspired certain Bond villains, most notably Le Chiffre in Casino Royale. Besides Le Chiffre’s bloated appearance, the journalist and historian Ben Macintyre argues that Fleming gave his first villain Crowley’s sadomasochism, writing, “When Le Chiffre goes to work on Bond’s testicles with a carpet-beater and a carving knife, the sinister figure of Aleister Crowley is lurking in the background.”

In the case of Crowley, fiction is probably the best vehicle for dealing with his eclectic life. Always more myth than man, his hold on us still is mostly due to the sensationalized stories that were common so many years ago. Antichrist, devil-worshipper, drug fiend, sadist — Crowley wanted us to think that he was all of these things, and in reality he certainly indulged in every whim or caprice, few of which could be called good, Christian fun. A libertine at best and a criminal at worst, Crowley remains the archetype of the evil occultist, no matter whether or not it’s all true.

Benjamin Welton is a freelance writer based in Burlington, Vermont. He prefers “Ben” or “Benzo,” and his writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Crime Magazine, The Crime Factory, Seven Days and Ravenous Monster. He used to teach English at the University of Vermont, but now just drinks beer and runs his own blog called The Trebuchet.

KEEP READING: More on Writers

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER AND FOLLOW BLACK BALLOON PUBLISHING ON TWITTER, FACEBOOK, TUMBLR AND MEDIUM.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©