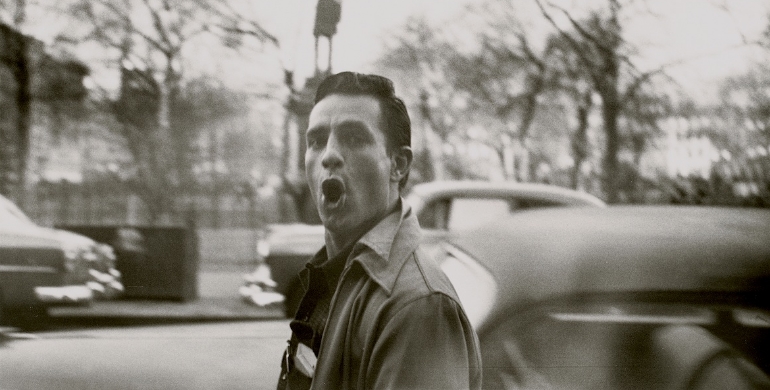

The Infrarealists in Mexico City, 1976 (via Wikimedia Commons)

The Savage Detectives by Roberto Bolaño thrust these poets into the mainstream, but who were they really?

When Los Detectives Salvajes (The Savage Detectives) was published in 1998, Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño was catapulted from obscurity to fame. He soon found himself on the receiving end of rave reviews and the Spanish-speaking world's heftiest literary prize, the Romulo Gallegos. Then, a few years after his death in 2003, translator Natasha Wimmers dragged the novel kicking and screaming into English, an accomplishment hailed as a major literary event and sparking renewed interest in the "visceral realists" thinly fictionalized in Bolaño's most autobiographical work. But who exactly were these poets beyond the confines of The Savage Detectives?

Roberto Bolaño (via Picador)

“Dada a La Mexicana”

The term infrarealism references the radiant energy just beyond the scope of visibility, known as infrared. Neither a school of realism or an unreservedly surrealist effort, the “Infras,” as they were sometimes known, kept one foot on the ground and the other in the realm of dreams. In an interview with BOMB Magazine in 2001, Bolaño summed the movement up thus: “Infrarealism was a kind of Dada a la Mexicana. At one point there were many people, not only poets, but also painters and especially loafers and hangers-on, who considered themselves Infrarealists. Actually there were only two members, Mario Santiago and me.” This sweeping dismissal is classic Bolaño (Isabel Allende famously labeled him “an extremely unpleasant man”) but does a disservice to the dozens of poets and artists associated with Infrarealism in the few short years of its existence.

Unfortunately, the passage of time and the turmoil of the era has erased much of what may have been known about these rebel poets. Information pursuant to them is scarce, especially in English, and what is available to us is owed to the work of a few diligent translators, Wimmer not least among them.

The Savage Detectives, Wimmer writes in the introduction to the Picador edition, "lovingly resuscitates the characters, the love affairs, the squabbles, the pettiest details of Bohemian Mexico City, around 1976." Readers familiar with the book will know already that its two protagonists, Arturo Belano and Ulises Lima, are doppelgangers: the former for Bolaño himself and the latter for the aforementioned Santiago. But aside from Arturo and Ulises, we’re introduced to an ensemble cast of scribblers and artists — the transformed personas of real-life Infrarealists.

“They Say the Infrarealists Beat People Up”

The Infrarealists were better known for disrupting readings than for their own writing. In an interview translated by Altar Piece, Santiago offered a glimpse into the mindset of the Mexican establishment at the time:

In 1975 I founded the Mexican Infrarealist movement. Around then they started to get sick of me, because I was confronting Pacheco, Monsivais, everyone I know of. ... Sergio Mondragon had to refused to give me a job because I’m an Infrarealist. They say I sabotage readings. They say the Infrarealists beat people up. And those idiots allege that I don’t know how to write. Motherfuckers.

Mario Santiago (via Wikimedia Commons)

Carmen Boullosa, a Mexican writer contemporary with the Infrarealists, paints a complicated portrait of the tensions fueling the Infrarealist’s behaviour. In regard to their famous antagonism towards Octavio Paz, she writes: “Paz was full of praise for the avant-gardes who had been so fond of manifestoes and had himself been closely associated with the Surrealists.” But the Infrarealists, variously composed of anarchists, idealists and disillusioned communists (Bolaño was an ex-Trotskyist himself), thought Paz and his associates were too close to Mexico’s ruling party, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party).

The shadow of 1968 looms large over Mexican society: This was the year when the PRI-led government massacred hundreds of student protesters at Tlatelolco Square in Mexico City. Consequently, the antipolitical tenor of Infrarealism struck a chord with many of the young people of the capital in the ‘70s. And while Bolaño and Santiago’s hijinks may have done little to disrupt the PRI’s entrenched position in the Mexican art world, it did earn them a certain kind of infamy.

The Manifestos

According to Altar Piece, there are at least three Infrarealist manifestos, all penned between 1975 and 1976 in Mexico City. The first was written by Jose Vicente Anaya, the second by Santiago and the third by Bolaño. (Confusingly, Bolaño's piece is subtitled "First Infrarealist Manifesto," which likely reflects an inflated notion of his own importance.)

Jose Vicente Anaya (via Circulo de Poesia)

Bolaño’s manifesto, the most famous of the lot, was published when he was only 23. It reads as a scathing indictment of the artistic community and the “good bourgeois culture.” He urges the reader to break away from normalcy (“try to abandon everything everyday”), and emphasizes the importance of sexuality and conflict (“for architecture and sculpture, the Infrarealists start from two points: the barricade and the bed”).

The common thread of each manifesto is something akin to absurdist militancy. Anaya insists that “conformists suffer from sanity and good sense”; Santiago advocates “converting conference rooms into firing ranges”, and Bolaño, with the post-’68 hangover of Mexican civil society in mind, issues a warning: “Raise arsonist kids, get burned.”

Both of the latter poet’s manifestos pay open homage to Andre Breton, the founder of Surrealism. All three pieces are endlessly quotable, although it’s apparent in tracing the sequence of Anaya-Santiago-Bolaño that there is an increasing distance from traditional Marxist ideas into more complex notions of a radical break.

Broke and Scattered

“With the political and economic tragedies of the region” Boullosa writes, “the literary circles broke and scattered, the publishing houses collapsed and Mexico City stopped being Latin America's sounding board. The youngest took their cues from the gringos—they judged the panorama of Latin American writing by which books had become hits in English translation.” In this way, the short-lived movement of Infrarealism came to an untimely end. Bolaño and Santiago left for Europe in 1977, with the former never to call Mexico home again.

Many questions remain about the Infrarealists. The Wikipedia entry for The Savage Detectives includes a lengthy table corresponding each of the characters to their real-life counterparts, but the majority of the links are missing, either yet to be written or their stories lost to time. Who, for instance, were Mara and Vera Larrosa, the sibling artists vibrantly fictionalized as the Font sisters?

Bolaño’s posthumous fame will surely guarantee a sustained interest in Infrarealism for years to come. But hopefully these efforts can shed a little light beyond his work and Santiago’s, and highlight the contributions of the numerous other writers and artists involved in their worlds.

Paul Murufas lives and writes in Long Beach, California. He is the author of dystopian's codependent syndrome (Mess Editions). His second collection of poetry and art, The Nihilist Romantics (Be About It Press), is free to read here. You can get in touch with him on Tumblr or via email at paulmurufas@gmail.com.

KEEP READING: More on Writers

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER AND FOLLOW BLACK BALLOON PUBLISHING ON FACEBOOK, TWITTER, TUMBLR AND MEDIUM.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©