Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by J. K. Rowling (via Emsworth)

“It takes a great deal of bravery to stand up to our enemies, but just as much to stand up to our friends.” — Albus Dumbledore

I absolutely love the world of Harry Potter and always will. Even as I’ve grown into an adult-ish person, their thrills and emotional devastation still hold up, and J. K. Rowling’s fantastic wit and solid life advice actually resonate more with age. That’s not to say the series is without its flaws. Sure, the Slytherins are all unfairly drawn as thuggish, and there’s no reason why every door shouldn’t be charmed with the Alohomora-proof enchantment (basically making them pick-proof). Also, far too many adverbs.

Endings shouldn’t take ownership over entire serieses, and resolutions are often damned from the start. That said, investment breeds hope for a satisfying send-off — and Harry’s end is a tricky one. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, the seventh and final book in the series, was met with a variety of opinions from critics and fans. With a dramatic break from the series’s precedent structure, the slaughter of fan-favorite characters and tons of plush toy merchandising, it can be a tough book to rank. But here we are, seven years to the day of its publication, long enough for it to be rooted and for us to seriously consider the question: Is the ending of the Harry Potter series any good?

Of course, that’s a flawed question, answered differently by everyone you’d ask. But in an internet-fueled world obsessed with endings, a world where fans want a conclusion the moment they start something, how is it that the reputation of Harry Potter seems to stand as a whole, not defined solely by its ending?

Because it was a decade-long journey. Even if you came late to the Potter party, this wasn’t a three-books-in-three-years outing like every franchise that isn’t A Song of Ice & Fire. “Whatever happens in the last of these brilliant adventures may matter less, for the millions of children who grew up with Harry Potter, than the end of his companionship,” wrote The Guardian of The Deathly Hallows. By that logic, didn’t everyone want things to work out for Harry and his friends — our friends? That emotional investment made the final book more doomed for failure (can't please everyone, and certainly not when they're taking it so personally), but also ensured that it could never take the entire series down; you don’t renounce your fond memories if your friends end up in a bad way.

New cover of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (via Buzzfeed)

Another challenge in Potter’s final installment was to keep it a story, not just a checklist of inevitable eventualities. Its ending had to both satisfy and surprise us — no easy task when millions of fans have spent years combing for theories.

From the start of Sorcerer’s Stone, it was assumed that the tale would end with a showdown between Harry and Lord Voldemort, presumably with Voldemort’s demise (because no one actually thought, after 10 years, Rowling would let wizard Hitler blow up a boarding school filled with children and then just move on).

More up in the air was Harry’s fate. The kid had been through a lot, so I was all in favor of letting him finally catch a break. Yet there were complaints that Rowling had her cauldron cake and ate it too by “killing” Harry and then un-killing him. New York Magazine’s review, “Harry Potter and the Ignominious Cop-Out,” slammed the final book for many reasons, amongst them was Rowling “owing us” the death of her bespectacled hero. The review stated: “In an MSNBC survey of fan reactions to Deathly Hallows, a 10-year-old who claims to have read the entire series eight times observed that, for his taste, the final book leaned a little too heavily on coincidence. I believe this tells us something important.”

A popular theory found on MuggleNet and elsewhere posited that Harry was a Horcrux (an object which stores part of a person’s soul, protecting him/her from death), and that would play a role in Voldemort’s demise. This happened, but much of what kept the final showdown’s execution from being totally predictable came from the conceit of the Deathly Hallows (the powerful Elder Wand, the Resurrection Stone and the Cloak of Invisibility), most of which was information withheld until the last book.

For a series so good at introducing unassuming plants that would pay off tremendously later, it’s hard to ignore the last-minuteness of the Deathly Hallows. Critics weren’t short on pointing this out either: The same Guardian review fairly calls the Hallows “some nifty plot accessories that allow for all kinds of crises, personal challenges and protracted revelations” — again, attempting to balance the need to both satisfy and surprise readers. For me, the newness and even clumsiness of the Hallows would’ve read as more annoyingly convenient if they weren’t so seamlessly representative of what became one of the series's thematic backbones: the conquering of death as a place of acceptance rather than a foe to best. Once more, I was seeking emotional resonance more than storytelling mechanics.

I admit it’s hard to let go of the text. But in trying to think more maturely about its conclusion, I realize that even if Harry birthed a vampire baby, everyone came back from the dead and the whole story was something Hagrid started blathering about whilst drunk in the Hog’s Head, it wouldn’t have mattered; this is still the most engaging reading adventure I have ever been on. In fact, studying the “strength” of its end may be like the Hallows themselves: the stuff of persnickety technicalities that aren’t as crucial as the satisfaction of fulfillment.

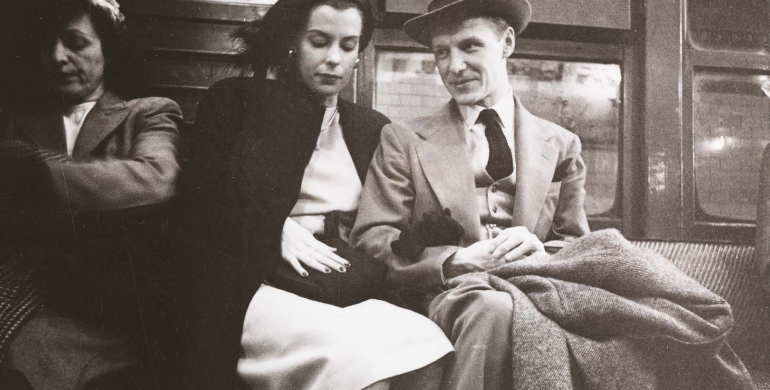

Because it all boils down to us getting what Rowling promised: We watched a boy grow into a man, and we grew with him. We saw the confrontation to end what started it all, and the way we got there, what that journey meant to us, that’s what mattered. It’s why mentioning the series doesn’t first conjure talk of who mastered which wand when, but of lessons on life and love. It's why Harry Potter will always be about three friends curling up by their favorite armchairs by the fireplace.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©