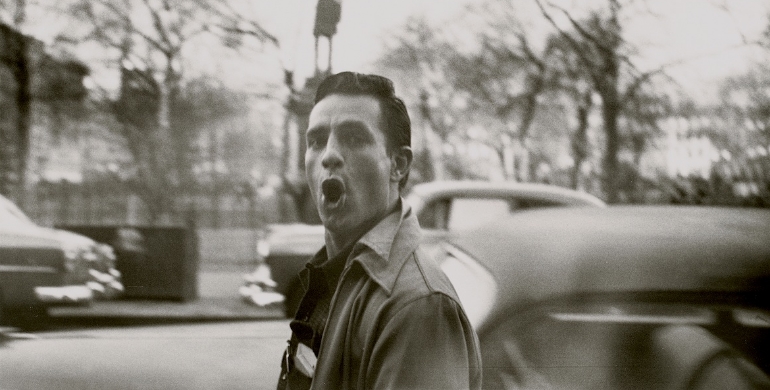

George Orwell (via Deviant Art)

Confession: I like George Orwell the novelist just fine, but he’s a paler character than George Orwell the journalist, essayist and critic. Orwell is best known for his final two novels: 1945’s Animal Farm and 1949’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, published just a year before his death. The fact that he wrote four other novels is rarely discussed, which probably has something to do with most people not having read Burmese Days, A Clergyman’s Daughter, Keep the Aspidistra Flying or Coming Up for Air, or even considering it. Worse still, Orwell’s incredible works of nonfiction are often relegated to the relatively small den of ardent admirers.

There’s a reason why Jeremy Paxman, the famed British broadcaster, noted, “If you want to learn how to write nonfiction, Orwell is your man.” In works like Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier, Orwell not only trains a sociological eye on those forgotten beneath the economic ladder, but he inserts himself in their struggle. Decades before Hunter S. Thompson’s deconstruction of journalistic objectivity, Orwell helped popularize “literary journalism,” combining nonfictional reportage with literary flourishes and artistic devices usually reserved for fiction.

George Orwell’s National Union of Journalists card, 1943 (via Net Charles)

The charm of much of Orwell’s nonfiction is his focus on timeless topics and his rigorous approach to even the most trivial of subjects, which are often one in the same, like the idealized English pub. (What’s more timeless yet still trivial than a bar?) For a man who was so consumed by politics that engulfed Europe before, during and after World War II, Orwell’s nonfiction is often characterized by a deep appreciation for those things which don’t change: village life, good beer, tea. In “A Nice Cup of Tea,” he manages to be both the deft critic and a doddering pensioner: “When I look through my own recipe for the perfect cup of tea, I find no fewer than eleven outstanding points. On perhaps two of them there would be pretty general agreement, but at least four others are acutely controversial.”

Of course not all Orwell’s nonfiction is so frivolous. In Homage to Catalonia, Orwell chronicles the devastation and suicidal in-fighting of the Spanish Civil War:

Chiefly I remember the horsy smells, the quavering bugle-calls (all our buglers were amateurs — I first learned the Spanish bugle-calls by listening to them outside the Fascist lines), the tramp-tramp of hobnailed boots in the barrack yard, the long morning parades in the wintry sunshine, the wild games of football, fifty a side, in the gravelled riding-school.

Orwell’s Spain is a dirty, ugly place, but also a place of hope and of political awakening. “I have no particular love for the idealized ‘worker’ as he appears in the bourgeois Communist’s mind,” Orwell writes in Homage to Catalonia, “but when I see an actual flesh-and-blood worker in conflict … I do not have to ask myself which side I am on.” This focus on real-world human beings instead of propagandistic caricatures would find its apotheosis in his final novel, but before Nineteen Eight-Four, Orwell had already shown the world the harsh realities of injustice and totalitarianism. And he had done so as a brilliant English journalist with a love for Charles Dickens (“Dickens is one of those writers who are well worth stealing”) and a passion for tea.

Benjamin Welton is a freelance writer based in Burlington, Vermont. He prefers “Ben” or “Benzo,” and his writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Crime Magazine, The Crime Factory, Seven Days and Ravenous Monster. He used to teach English at the University of Vermont, but now just drinks beer and runs his own blog called The Trebuchet.

KEEP READING: More on Writers

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©