I am partial to conspiracy theory. According to Zizek, this comes from a human need for disaster to be explained with meaning. According to Netflix, it means I prefer “Fight the System” films (not to mention “Movies with a Strong Female Lead”). Either way, having recently stumbled upon a 2006 documentary called Technocalyps, I want you to know that the robots are coming and they are going to enslave us, and the way they are going to do it is by tricking us into falling in love with them. Or at least that is what I’ve gathered in the last week — from Technocalyps, and from the novel A Working Theory of Love by Scott Hutchins.

I am only half kidding. In the film there is an old scientist in a lab coat who speaks with that special glint of madness in his eyes as he recounts an experiment that involved switching the head of a monkey to another body, where it managed to live for 14 days before the brain rejected it. The monkey, he claims, had the same personality on his new body. Which is to say that the future of mankind is a kind of “head swap,” or at least, as far as he’s concerned, “that consciousness can be transplanted.”

But what constitutes our consciousness? Is it all in our heads? Does our body have nothing to do with it? And along that sort of thinking, let’s say the path to my soul involves more brains than bod: does that mean it’s possible that I — a living, breathing human being — could feel a true, deep emotion for a machine? According to the computer scientists in A Working Theory of Love (published by Penguin last October), it’s possible; the machine just needs to be imbued with a “transplanted” or “uploaded” human spirit.

Hutchins’s book follows a tech race to design a computer that can outsmart a Turing test (i.e. whose intelligence is indistinguishable from a human’s). The computer, named “Dr. Bassett,” communicates through IM, chatting casually with those who work on his development about their daily lives and routines. But like an office pal who becomes a real friend, eventually these scientists begin sharing more of their hopes and feelings — not because they are the needy types (we all are), but because “drbas” (his IM name) is programmed to listen attentively, and he responds thoughtfully. Unlike a real person on the other side of an IM or text, he is not distracted by an outside world. And the more an individual user speaks to him, for example “frnd1,” the more he learns about her, making the human/computer exchange more complex, with inside jokes and secrets. A real, emotional connection — on the human side, at least.

Sounds like some sort of puke-worthy dream guy from a chicklit drama, right? But maybe it would actually be satisfying. Perhaps not in a holistic way, but in the same way an iPhone is a perfect companion on a bus ride, or in the bathroom, or when you sit alone at a bar.

What if someone took all that stuff we babble at each other, the thoughtless likes, lol’s and your mama’s and made it the beginnings of a synthetic brain? Someone (something?) to comfort and love a future you, a potential almost-mate, a companion to pass your time with as your performance continues to be one-upped by the progress of machines…

Yeah, whatever, it might happen, so what? A new world is coming, or so one of the scientists in Technocalyps says, and “the winners may be some transhuman thing.”

What bothers me, being less of a transhuman and more of a hippie, is how plausible the “online chat” measure of humanity in Hutchins’s novel feels. Look at us. We’ve already uploaded ourselves. How are you reading this? And if love, friendship and desire can be born that way, who’s to say that they can’t stay there, giving you just enough satisfaction, surviving in that ephemeral flicker of a backlit screen for years?

I know — I’m creeping myself out. But seriously, here I am sitting in front of a glowing box, focusing my consciousness into a screen. And what do I want out of it? Maybe something you could call love. Some automatic feedback. A chat-bot fan.

At one point, Toler, the money-loving scientist from A Working History of Love says, “Is love just a random emergent property? Maybe. Maybe it’s a social construct. Who knows. What’s important from our point of view, again as businessmen, is that even if love is an illusion, it’s an illusion more powerful than reality.”

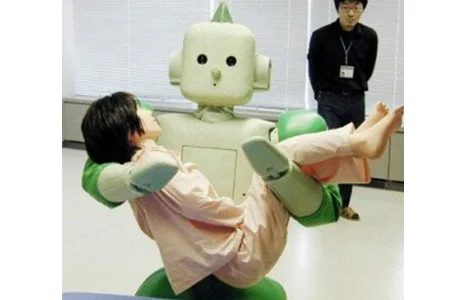

Which means, I guess, read the fine print before you go all the way with a robot. Also, her boobs are totally fake — but so is her, well, everything. And perhaps that's what makes her so approachable.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©