Last Sunday in the Flatiron District, I ventured through a pair of glass doors whose red handles formed the shape of the number pi. A numeral was on the loose, somewhere inside the newly opened Museum of Mathematics. By forming teams and solving a series of puzzles, we could compete to recover it.

Puzzle hunts are a well-established phenomenon, with the two-day MIT Mystery Hunt reigning supreme among them and attracting a thousand solvers to campus every year. New York has seen a few puzzle hunts of its own, from the bygone Haystack to the nationwide DASH. But no local venue could be as appropriate as MoMath, the nation’s first museum dedicated to math and math evangelism.

Referees shepherded us downstairs, past a giant suspended hyperboloid and paraboloid, and here the floor began to respond to our feet, glowing pink circles and green lines appearing where we stepped. Spheres lit up in rainbow hues at the touch of a hand and sent forth music.

I ripped apart our packet of puzzles and doled out the pages to the team I'd brought — a climate-modeling scientist, a civil engineering professor, an electrical engineering grad student, and a computer programmer. We huddled over our pencils and started hunting.

“Wait, how do I do this?” my friend wondered aloud.

I gave him a look. He was disrupting my concentration.

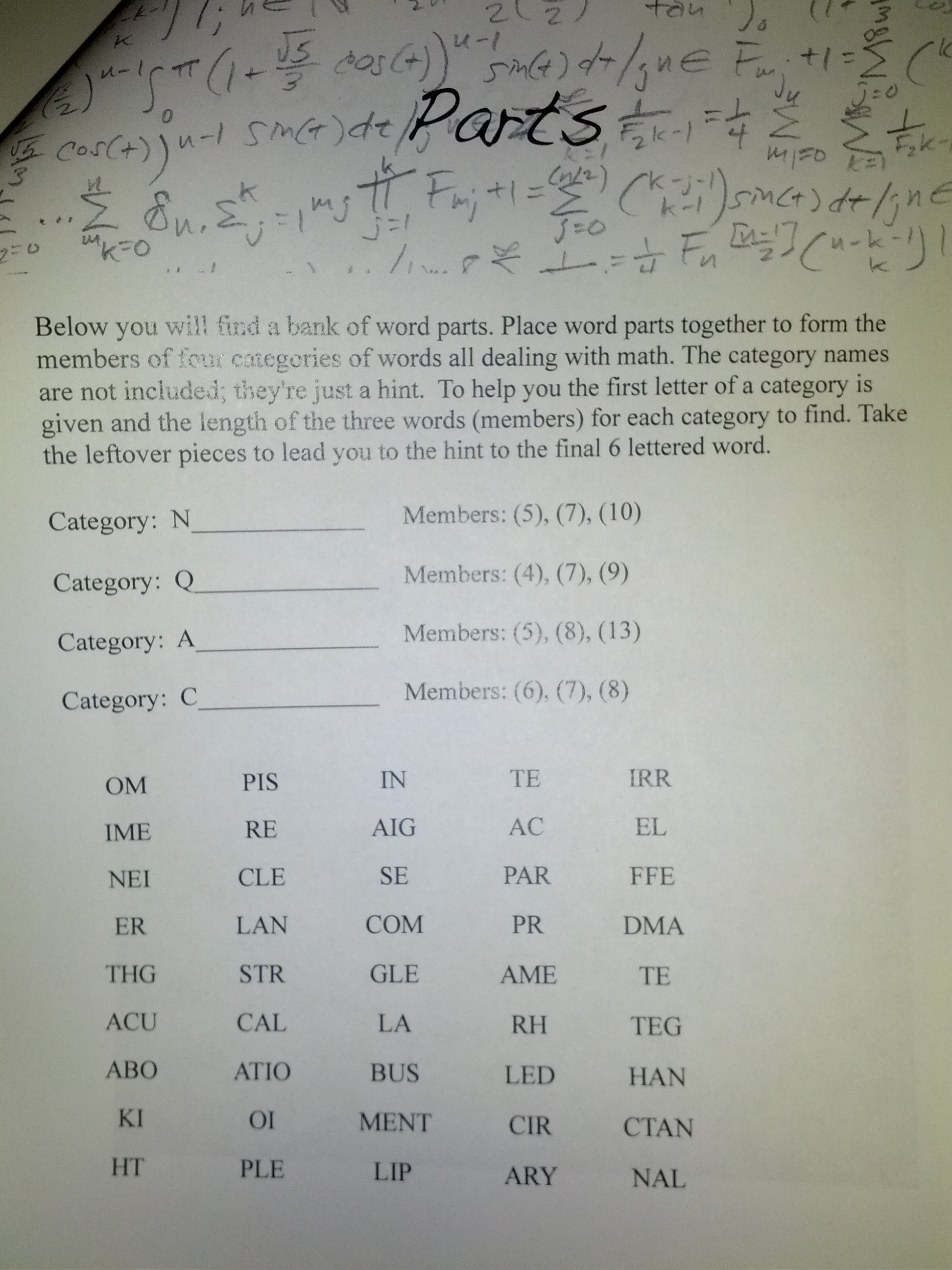

More than 30 teams — over a hundred seekers, young and old — had settled in groups across the tables and floors. Designated hint-givers, their nametags reading "Game Control," walked among us. Some of the puzzles were familiar, like a KenKen or a modified crossword and word search, but the best came with no instructions at all. A series of equations lacking operators was entitled Undivided and Nonplussed. We took this to mean that multiplication and subtraction symbols should be inserted in such a way that the left side of each equation equaled the right. But that couldn’t possibly be the final answer, because the answer to each of the twelve puzzles had to be a single word. It took a leap of insight to realize [Spoiler alert!] that the multiplication dots and subtraction dashes should be read as Morse code.

Another instruction-free puzzle consisted of a dozen strings of five letters each, such as LGEBR and NSULI. I realized that these were all the middles of seven-letter words. I wrote out the twenty-four missing letters and discovered that there were only seven unique letters among them. On a hunch, I calculated the frequency distribution and noted that the A was double-weighted. I therefore wrote it down twice, next to the other letters: A A C I N O R T. After several minutes of furious anagramming, I jumped up in a rush of elation. Ninth puzzle solved. Three to go.

Once we had completed all twelve, we were handed a baggie bearing three sets of green plastic pentominoes. Again, no instructions. First we had to deduce which of the three sets to use. After that we had to remember that the twelve pentominoes make a rectangle, and to fumble through assembling the tiles. Now the engravings on the pieces spelled out a phone number, which we dashed upstairs to dial, alighting upon cell-phone reception next to a wide silvery mosaic of holograms. A voice recording intoned, “Congratulations.” Alas, three hours had elapsed. The winning team had beaten us by thirteen minutes.

Coming in second wasn’t so shabby considering that only four teams, out of more than thirty, finished at all. The champions were a software engineer, a chemical engineer, a string theorist, a bioinformatician, and a management consultant. Most of them had traveled from out-of-state to play. Their prize: a set of Mobius strips created by the Lego sculptor Eric Harshbarger.

As for us, sometimes it's sweeter to remain a little bit unfulfilled — to stay hungry for the next hunt.

All photos by the author

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©